Where in the world will you find an impressive collection of Ukrainian Easter eggs, a Cold War memorabilia-filled four-storey bunker and the cast of a 12,000-year-old woolly mammoth?

Answer: In Canada’s lesser-known museums.

Although our country boasts several world-renowned institutions, you’ll discover countless fascinating artifacts in Canada’s smaller, specialty and sometimes off-the-beaten-path museums.

Here are several discoveries that we’ve enjoyed, to give you an idea of the diverse treasures preserved in collections from coast-to-coast-to-coast.

Hand-painted eggs

With Ukraine dominating the news this year, the Ukrainian Museum of Canada is especially relevant. We visited the Saskatoon branch. (Other branches are in Edmonton, Winnipeg and Toronto.)

Amid displays of Ukrainian heritage, folk art and traditional clothing, we discovered dozens of intricately patterned, colourful and painstakingly hand-painted pysanky (Ukrainian Easter eggs). Some – brought to Canada by early immigrants – are more than 100 years old.

Pysanky-making workshops – held for two weeks prior to Easter in the Saskatoon branch – teach participants how to paint the decorative symbols using wax resist techniques. Year-round, you can buy kits with instruction guides, design sheets, beeswax, tools and dyes. The gift shop also sells beautiful pysanky created by Canadian artists. umcyxe.ca

Top-secret bunker

If Russia’s threats of nuclear attacks during its Ukraine invasion bring back memories of the Cuban missile crisis, the Diefenbunker in Carp, west of Ottawa, is a must-see. Top-secret for years, the four-storey bunker was named after Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who commissioned it in 1959 to house key government and military officials in the event of a nuclear attack on Canada.

Built to withstand a five-megaton nuclear blast from 1.8 kilometres away, the steel-and-concrete structure is Canada’s strongest building. Its 358 rooms could safely shelter 535 people with enough food for 30 days.

Our eyes widened during a guided tour of the underground mini-city, as we viewed Geiger counters, decontamination rooms, a hospital, cafeteria, dental clinic, CBC radio studio, Bank of Canada vault, electronic equipment, meeting rooms and bedrooms, including one for the prime minister. Civil defence publications, Cold War archives and posters fill the extensive library.

The 100,000-square-foot nuclear bomb shelter operated until 1994, when it became a National Historic Site. The museum opened in 1998. diefenbunker.ca

Ice age mammals

We time travelled much further back in history at the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre in Whitehorse. Near the end of the ice age 30,000 to 16,000 years ago, lowered sea levels created a land bridge over the Bering Strait, allowing people and animals to migrate from Siberia to the Yukon – an area called Beringia.

Wall murals, skeletons and replicas portray landscapes and the mix of familiar (caribou, muskox and grizzly bears) and now-extinct animals that roamed Beringia’s treeless plains. Scimitar cats occupied the Yukon more than 20,000 years ago. A model of the formidable 200-kilogram feline predator depicts its oversized canine teeth.

Craning our necks, we viewed the skull of a plaster cast of a 12,000-year-old woolly mammoth. The four-metre-high adults had curved tusks that grew up to 3.5 metres long and weighed up to 100 kilograms each.

We examined a woolly mammoth tusk unearthed in the Dawson gold fields. By studying its growth rings, scientists determined that it was about 25,000 years old. beringia.com

Octopus bags

The 40,000 objects in downtown Whitehorse’s MacBride Museum also include mammoth tusks, as well as Klondike Gold Rush memorabilia and wildlife displays. (Will your head fit into a polar bear’s mouth? Discover the answer at the hands-on exhibit of animal skulls!)

Among the Yukon’s 14 First Nations arts and crafts on display are some fascinating beaded octopus bags. Named after the eight-armed mollusk, the bags were originally used by medicine men who stored traditional medicines in each finger. They were later used as ceremonial dance aprons and beautifully decorated bags to carry tobacco, pipes and flint for starting fires. macbridemuseum.com

Birch bark-biting

Located 15 minutes northeast of downtown Saskatoon, Wanuskewin Heritage Park combines an archaeological site, indigenous cultural interpretations and performances, indoor exhibits and galleries.

Works by contemporary and traditional First Nations artists include paintings, sculptures, beadwork, jewellery and porcupine quill-decorated baskets.

The unique birch bark bitings by Cree Elder and residential school survivor Sally Milne are especially impressive. Using only her teeth to bite hand-peeled birch bark, she creates distinctive pieces of art. wanuskewin.com

Inuit culture

Although it’s a small building, Churchill Manitoba’s Itsanitaq Museum houses impressive displays of 1,300 items from a collection of 4,800 Inuit artifacts and works of art. Itsanitaq means “things from the past – objects, events and stories.”

Most outstanding are the whalebone, walrus ivory, soapstone and muskox horn carvings. Visitors can listen to audio descriptions of specific items on handsets. We especially enjoyed viewing handmade items from everyday Inuit life, including tools, sealskin boots and boats. travelmanitoba.com/directory/itsanitaq-museum

World’s only mooseskin boat

Much rarer than the sealskin boats in the Itsanitaq Museum’s collections is the only mooseskin boat ever preserved. For us, it was the highlight of the natural history, northern aviation, mining exhibits, Dene and Inuvialuit cultural displays in the Yellowknife, N.W.T. Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

A moose hide sign explained that, from the late 1800s to the 1950s, these boats transported people, dogs, meat, furs and other goods down rivers to the Mackenzie River and trading posts. Designed as temporary craft, the boats were dismantled after the journey. The hides were used for clothing and other items and the occupants returned home on foot.

By the 1950s, mooseskin boats had virtually disappeared. Elders, who still retained the knowledge and skills, decided to teach young people about this part of their heritage. In 1981, Gabe Etchinelle built the boat from eight moose hides, without nails, using only an ax, needles and knives.

Another moose hide sign shows its route from the construction site near the headwaters of the Keele River to the Mackenzie River and Tulita (formerly Fort Norman). A barge transported it to Yellowknife. pwnhc.ca

Largest Yukon River sternwheeler

Canada’s maritime history is also showcased in a Parks Canada museum inside the permanently docked S.S. Klondike in Whitehorse.

To prepare for our visit to the national historic site, we viewed outdoor interpretive panels – developed in partnership with First Nations along the Yukon River – and watched the 20-minute In the Days of the Riverboats video in the theatre.

They explained how life on the Yukon’s rivers changed for Indigenous peoples after the first steam-powered paddlewheelers arrived in the 1860s, carrying newcomers and their ways of life until the 1950s.

During our guided tour, a heritage interpreter recounted stories of life on the river. We learned how much wood was required to keep the paddlewheel turning, how captains negotiated the rapids and how the crew unstuck ships from sandbars. pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/yt/ssklondike

Viking ship

Newfoundland’s Norstead Viking Village also reflects Canada’s maritime past. The replica 11th-century port and commercial trading site features four historically correct buildings, costumed re-enactors and a knarr (Viking ship).

Inside the sod-roofed boathouse, Bjorn explained that the Vikings explored the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador in ocean-going traders such as this one. Built in Maine in 1996, the re-created 16.5-metre ship had an open deck and a canvas sail. Pointing at the planks, he noted that they were fastened with 2,700 rivets from an English bridge.

In the Norstead chieftain’s hall, other interpreters described daily life for the Vikings who settled in Newfoundland. We watched a woman spin sheep fleece into yarn with a whorl drop spindle. She explained how she knit the yarn into mittens, socks and hats with a needle made from moose antler. norstead.com

Living history museum

Just two kilometres from Norstead is another living history museum – L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site. Interactive displays in the visitor centre answer questions about Viking life and depict archaeological finds, including spindles and fragments of bone needles used by Norse women.

Inside one of the reconstructed sod buildings, we discovered a Viking encampment. Dressed in Norse costumes, Egil and Thora sat by the hearth and invited us to relax on sheepskin-covered benches on the other side.

After describing how they churned butter, cooked in iron pots and used the tools around them, Egil pulled out a wooden lyre and sang a song as he plucked the strings. For a few minutes, the music and surroundings transported us back 10 centuries. pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows

Creepy-crawlies

The living museum concept takes on a whole new perspective at the Bug Gallery in Edmonton’s Royal Alberta Museum. Even squeamish visitors become fascinated when they view and learn about the spiders, insects and other invertebrates that comprise 97% of the animal kingdom.

As we safely searched glass cases for camouflaged insects – inches from our noses – and viewed the social behaviour of paper wasps, we learned about warning colours, ambush predators and how invertebrates find mates and capture prey. The beauty, diversity and ecological roles of jungle nymph stick insects, rhinoceros beetles and scorpions soon captivated us.

The highlight for intrepid visitors is the opportunity to handle some species, including tarantulas, when staff and volunteers are available. royalalbertamuseum.ca/visit/galleries/bug-gallery

Building-sized exhibits

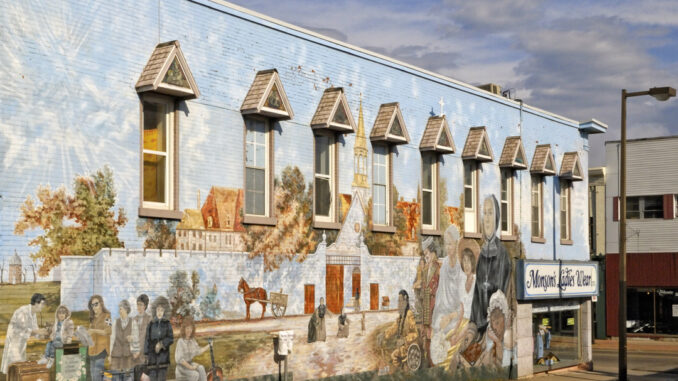

Whereas the Bug Gallery’s exhibits are smaller than the palms of your hands, other museum displays are as large as edifices. In Pembroke, Ontario, more than 30 giant canvases cover the buildings’ exterior walls. Painted by Canadian artists, these illustrate the history and culture of the city from 1828 to recent years.

Using a free audio tour (which can be streamed or downloaded) and a Pembroke Heritage Murals© map, we walked along Pembroke’s streets, exploring a bygone era. Mural topics are as diverse as the city’s history, ranging from old-time fiddling to street lights. (Pembroke was the first town in Canada to illuminate its streets with commercial electric lights.)

From 1828 to 1980, lumber was Pembroke’s main industry. The Timber Raft mural portrays loggers steering rafts made from white and red pine timbers along the Ottawa River rapids. From here, they followed the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City to ship the wood to European markets. The timbers were hewn square so that they fit more easily into the holds of ships.

One of the most unique Heritage Murals is a rare three-dimensional painting of Marguerite d’Youville, founder of the Grey Nuns and the first Canadian-born canonized saint. Photocell-illuminated cornices resembling stained glass windows span paintings depicting people for whom Marguerite cared in her mission. pembroke.ca/en/recreation-and-culture/pembroke-heritage-murals.aspx

Travelling displays

While Pembroke’s exhibits are permanent, many museums feature rotating temporary shows of artifacts on loan from private collectors and other institutions.

Whenever we plan museum visits, we always check their websites for these special exhibitions. They offer opportunities to view rarely seen items.

During a visit to the Prince Edward Island National Park Greenwich Interpretation Centre, for example, we viewed an engrossing and informative display of Mi’kmaq baskets from the Ray Sark Collection.

In addition to admiring the beautiful baskets, we learned about the tools and techniques for weaving them from ash, maple, sweetgrass and other materials.

pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/pe/pei-ipe/visit/greenwich/

So much choice

This summary barely scratches the surface of Canada’s numerous museums.

The Canadian Museums Association currently lists 2,752 museums in its directory, in every province and territory. Their categories include aeronautics, agriculture, anthropology, archaeology, arts & leisure, children’s museums, community & regional, cultural centres, historic sites, industry & trade, living history, maritime, military, music & performing arts, natural history, religion, science & technology, sports and transportation.

museums.ca/site/aboutthecma/services/canadianmuseumdirectory

The directory is proof that, no matter where you’re travelling in Canada, you’ll find many opportunities to discover hidden treasures.

by Barb & Ron Kroll, who publish the trip-planning website www.KrollTravel.com